The Thinly Veiled Bigotry of Book Bans

February 27, 2023

In schools across Florida, bookshelves that were once replete with insightful and important stories now hold nothing except a layer of dust. Children in the middle of discovering the knowledge held between a book’s pages are left empty-handed and confused, while teachers fear the possibility of termination and even prosecution for putting books into the hands of their students.

Governor Ron DeSantis championed the bill at fault for the recent uptick in book bans, which has a questionable track record of targeting books with LGBTQ+ characters as well as characters of color. In July of 2022, DeSantis signed House Bill 1467, which aims to ban books that are “pornographic” or “not suited to student needs”.

The bill also requires books to be approved by a “media specialist” before being allowed to remain in school libraries. Unfortunately, vagueness breeds bias, which runs rampant in wake of the bill being put into effect. Without specifying a clear checklist these books must follow, anything can be deemed unsuited for student needs.

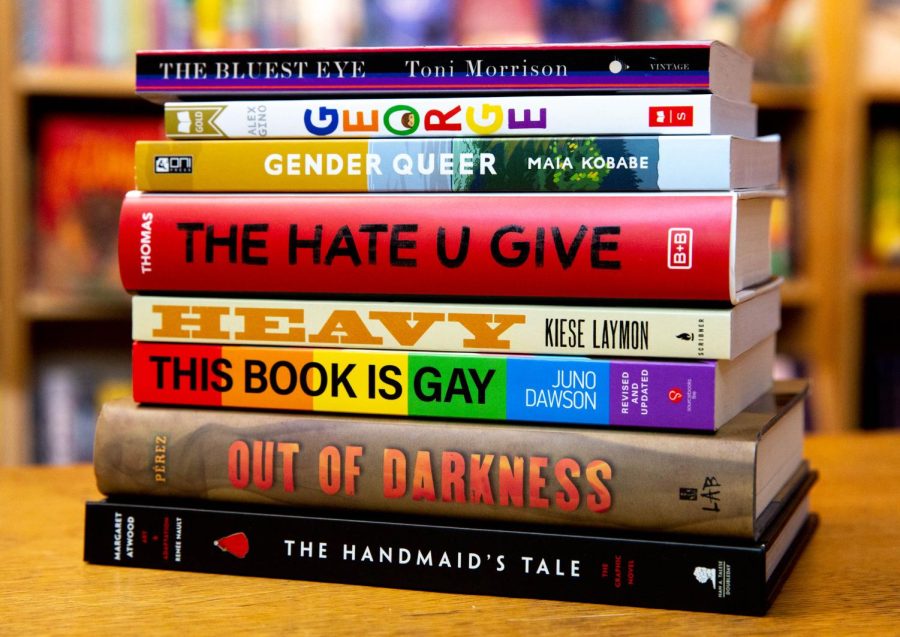

Books such as The Hate U Give, a young adult novel depicting the very real issue of police brutality, are caught in the eye of the storm in many schools across the Sunshine State. A picture book titled Everywhere Babies, which aims to teach children about infants and families of all diversities, is also found on book ban lists for depicting LGBTQ+ characters.

Is learning about the world around them not a student’s need? Stories depict life and truth. By keeping students away from books that accurately portray the people they’ll find in society, they will be faced with realities they don’t know how to understand when they are older.

Not only do book bans disproportionately affect books depicting LGBTQ+ and POC—people of color—perspectives, the bill itself also disproportionately affects low-income schools and students. Schools in low-income communities often do not have media specialists on hand every day of the week, which means they don’t have anyone available to examine the books placed under review.

Even schools that do have media specialists available aren’t getting through the thousands of books that need to be reviewed because of the vague stipulations. Students whose families cannot afford their own books can no longer get them from their schools, while media specialists are so overloaded that shelves have completely emptied and now remain that way.

Having to remove their books baffles and frustrates teachers, but they’re silenced by the fear and unease surrounding the situation. Although they often curate their classroom libraries with their own money and resources, most do not want to risk losing their jobs by defying the bill and giving their students books under review.

Even more frightening is the threat of prosecution. Apparently, the bill can get even vaguer, because it fails to outline clear consequences for teachers. Again, this holds space for interpretation, which certain school officials took with liberty and threatened violations could lead to a third-degree felony.

The burden of DeSantis’s hazy bill falls onto the backs of underpaid school faculty as well as students themselves. The bill creates an environment where students are being taught that reading is an activity that needs to be monitored. Choice has been lost and replaced with blurry limitations enforcing the idea that reading certain books warrants negative consequences for students and their teachers alike.

Despite whatever DeSantis intended with this bill (which isn’t hard to conclude based on what else he preaches), his failure to specify logistics has turned Florida schools into places where the idea of reading becomes synonymous with consequence and uncertainty. Children walk into classrooms where they are taught where to hide from shooters, but not where to find books that will represent them and foster their sense of curiosity.

Without books, where will students turn when they have unvoicable questions? Evidently, they won’t be able to turn to their legislators for any sort of answers.